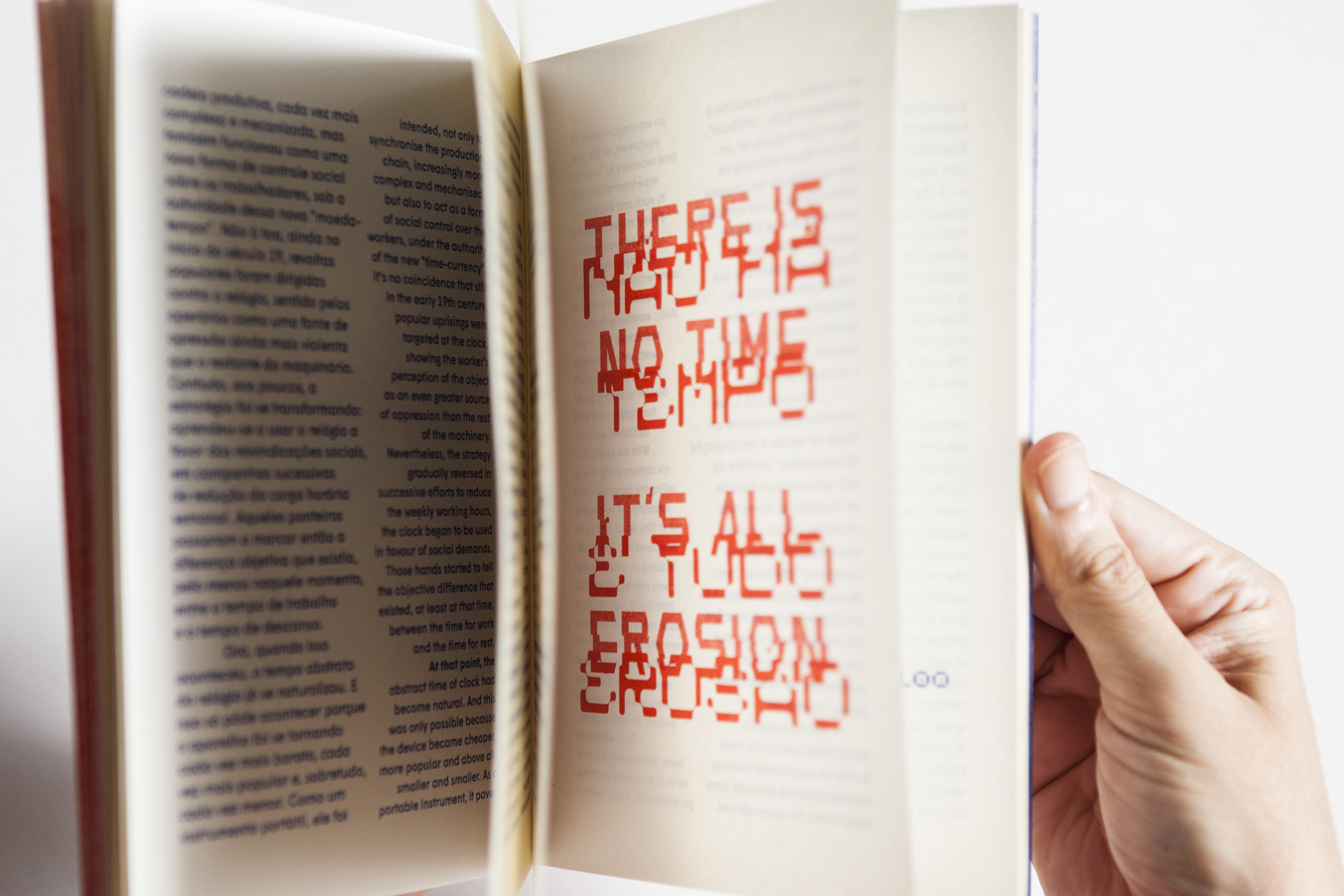

There Is No Time

It’s All Erosion

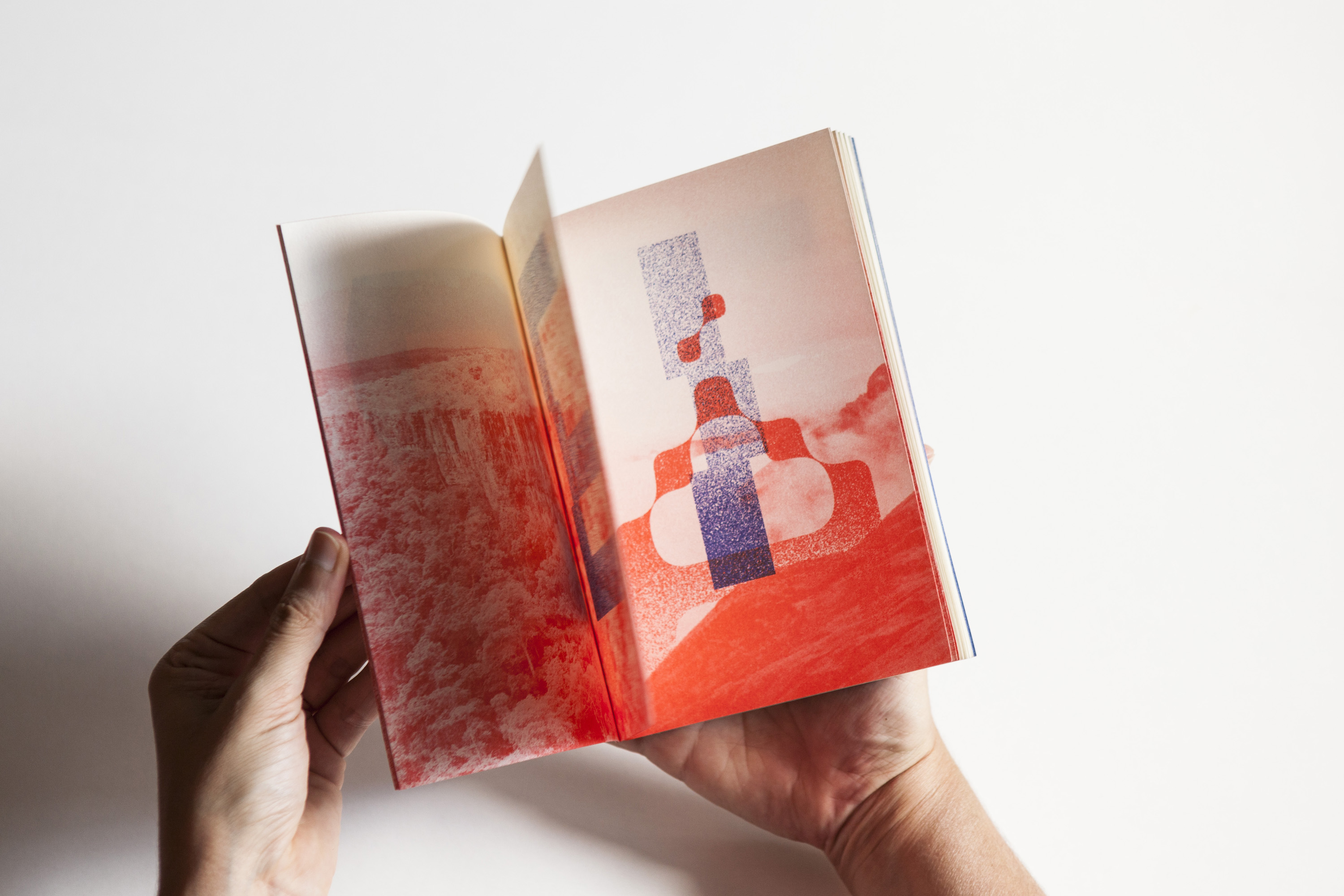

The publication There Is No time – It’s All Erosion proposes a short reading from the idea of a time naturalized as unique, the "abstract time of machines", contrasting with the erosive and sedimentary processes that point to the "geological time".

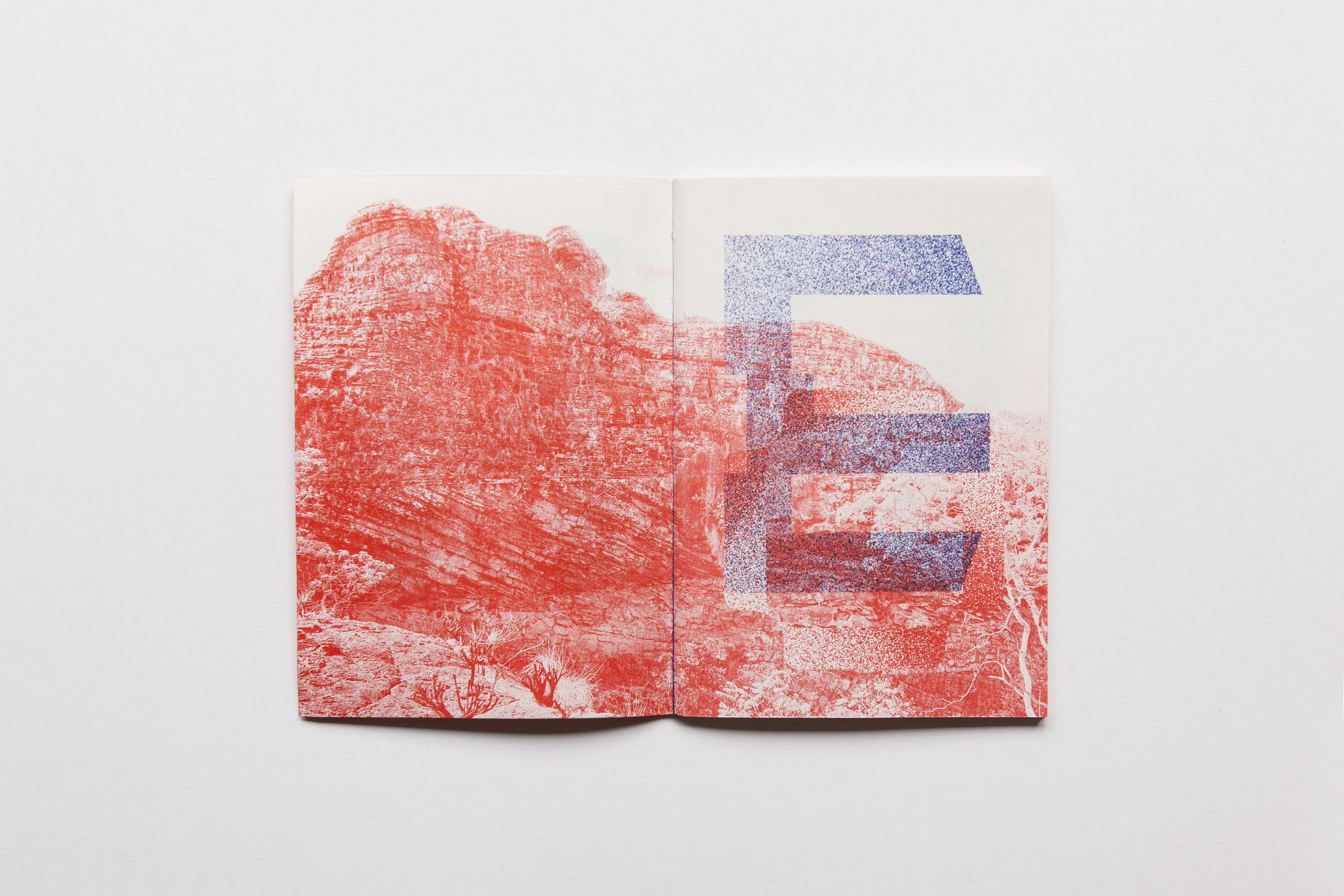

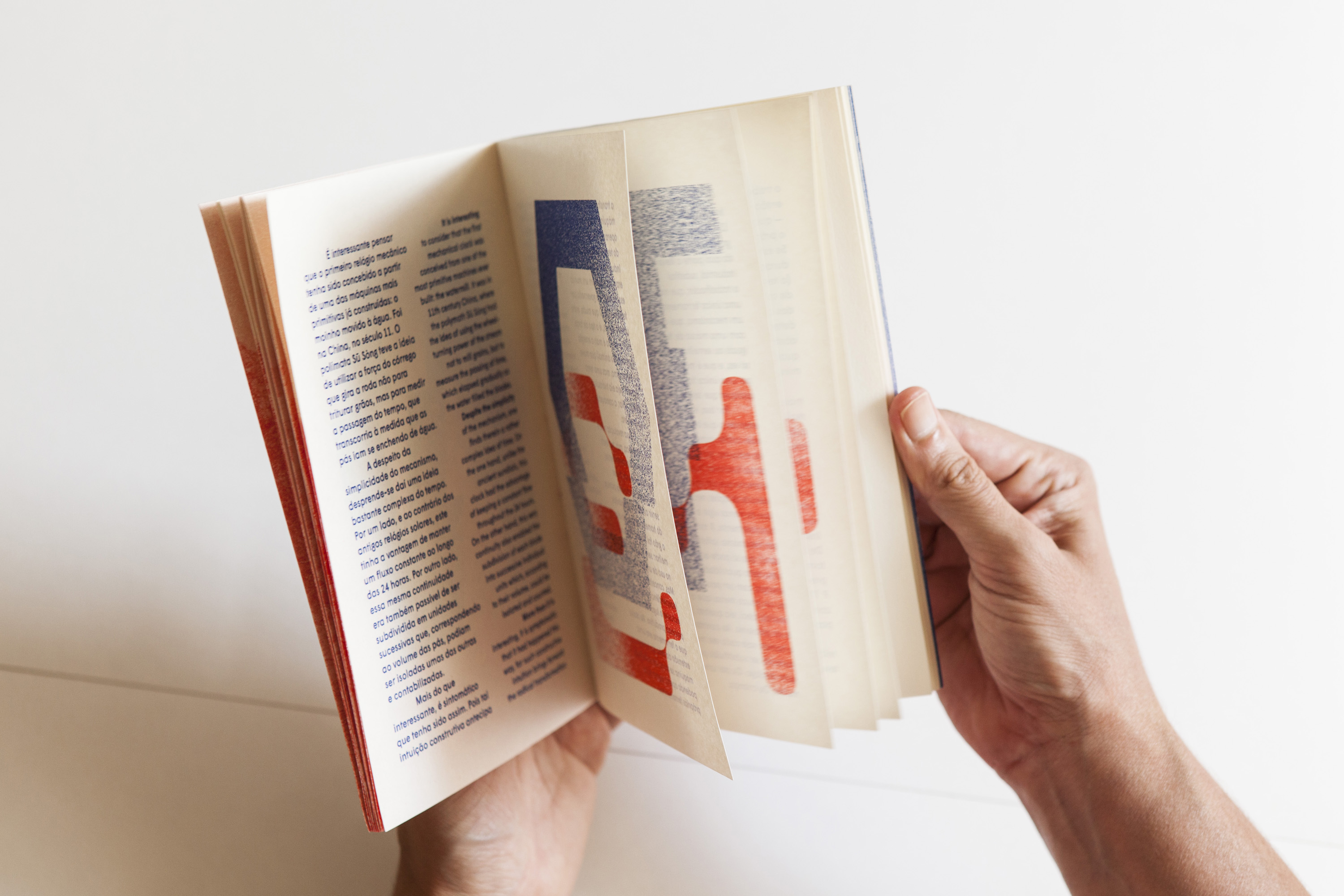

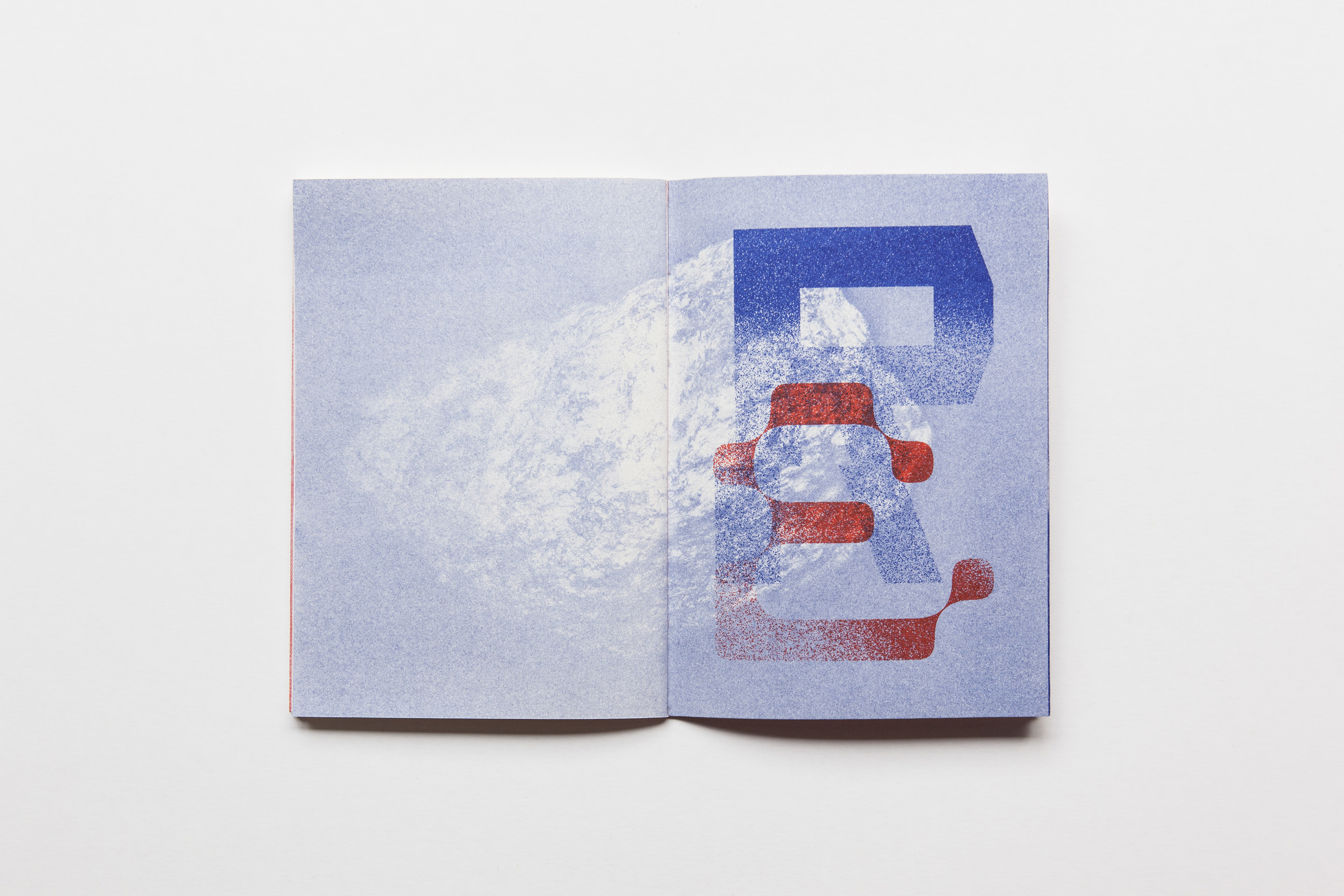

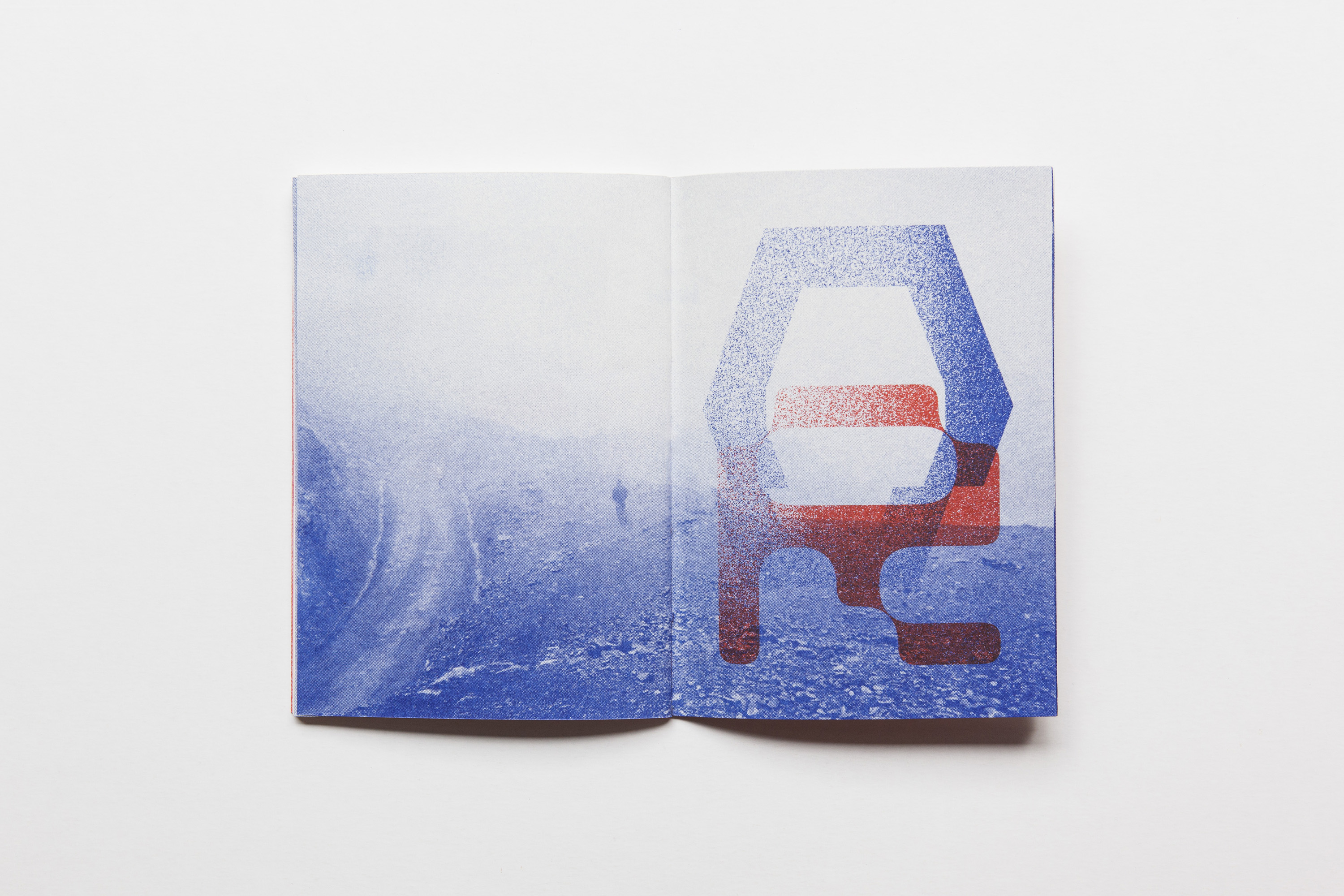

The photographic images of rocks that compose this visual essay were edited to go through a specific printing process, with reticles and saturation, in order to create traces of layers and an allusion to the "geological time". Douglas Garcia took the photos, made the research and edited the images.

The essay about the "abstract time of machines" was written by the visual artist Daniel Jablonski, invited by Edições Membrana. Marina Oruê’s graphic design, based on the publication’s title, explores the use of the letters in Portuguese and English highlighted by graphic layers suggesting the intertwining and simultaneity between the pages.

The publication was launched at Printed Matter's Virtual Art Book Fair (PMVABF), New York, February 25th to 28th, 2021.

The photographic images of rocks that compose this visual essay were edited to go through a specific printing process, with reticles and saturation, in order to create traces of layers and an allusion to the "geological time". Douglas Garcia took the photos, made the research and edited the images.

The essay about the "abstract time of machines" was written by the visual artist Daniel Jablonski, invited by Edições Membrana. Marina Oruê’s graphic design, based on the publication’s title, explores the use of the letters in Portuguese and English highlighted by graphic layers suggesting the intertwining and simultaneity between the pages.

The publication was launched at Printed Matter's Virtual Art Book Fair (PMVABF), New York, February 25th to 28th, 2021.

There Is No Time – It’s All Erosion

Marina Oruê, Douglas Garcia

︎︎︎publication

13 x 18,5 cm, 56 pages

print by risograph 2 colours:

medium blue, warm red

bilingual edition of 100 copies,

numbered Portuguese/English

images and edition, Douglas Garcia

graphic design, Marina Oruê

text by, Daniel Jablonski

proofreading, Mariana Moura

translation, Juliana Lopes

printing, Entrecampo

São Paulo, SP, January 2021

Edições Membrana

Marina Oruê, Douglas Garcia

︎︎︎publication

13 x 18,5 cm, 56 pages

print by risograph 2 colours:

medium blue, warm red

bilingual edition of 100 copies,

numbered Portuguese/English

images and edition, Douglas Garcia

graphic design, Marina Oruê

text by, Daniel Jablonski

proofreading, Mariana Moura

translation, Juliana Lopes

printing, Entrecampo

São Paulo, SP, January 2021

Edições Membrana

A short essay, written on the request of Edições Membrana, about the ever-growing impact of technology upon our experience of reality. I relate a transformation on our perception of time caused by the clock in the 19th century, to the one operated by photography in space in the 20th century; as a way of pointing out the paradoxical place that machines occupy in Western societies: the more present they are, the less perceptible they become. But, once placed installed in our pockets, faces, or screens, they work as filters (properly invisible), replacing a concrete, qualitative, heterogeneous nature by its double, an abstract, quantifiable, homogeneous second nature, ready to be consumed, exchanged and accumulated. Just like money.

Daniel Jablonski, 2021

Essay for publication

There Is No Time – It’s All Erosion

Edições Membrana, São Paulo, SP

Daniel Jablonski, 2021

Essay for publication

There Is No Time – It’s All Erosion

Edições Membrana, São Paulo, SP

It is interesting to consider that the first mechanical clock was conceived from one of the most primitive machines ever

built: the watermill. It was in 11th century China, where the polymath Sū Sòng had the idea of using the wheel-turning power of the stream not to mill grains, but to measure the passing of time, which elapsed gradually as the water filled the blades.

Despite the simplicity of the mechanism, one finds therein a rather complex idea of time. On the one hand, unlike the ancient sundials, this clock had the

advantage of keeping a constant flow throughout the 24 hours. On the other hand, this very continuity also enabled the subdivision of each blade into successive individual units which, according to their volume, could be isolated and counted.

More than it is interesting, it is symptomatic that it had happened this way, for such constructive intuition brings forward the radical transformation which the

machines will, at a later instance, instil in our perception of time. Before the Western Industrial Revolution, those were exceptions in a world essentially governed by tools. What changes in their respect, is the kind of driving force they employ: it is no longer the human force or animal labour that moves the mechanism, but a natural force, stemming from water, wind, the sun, combustion, vapour, and so on.

This revolution is not only energetic, but functional. Apparently, judging from the results, the machine seems to still serve the purposes of man: in the end of the day, the grain was milled – and better yet, without the smallest effort in the operation of a tool. However, conceptually, this effortlessness changes everything, particularly where man stands in the production process. Whereas once the tools were the extension of a man’s hand, the machine now becomes his replacement, capable of independently operating its own tools.

This is what Marx points out in Book 1 from The Capital, in the chapter entitled

'Machinery and the Modern Industry': «The

machine, which is the starting-point of the industrial revolution, supersedes

the workman who handles a single tool, by a mechanism operating with a number

of similar tools, and set in motion by a single motive power, whatever the form

of that power may be»[1].

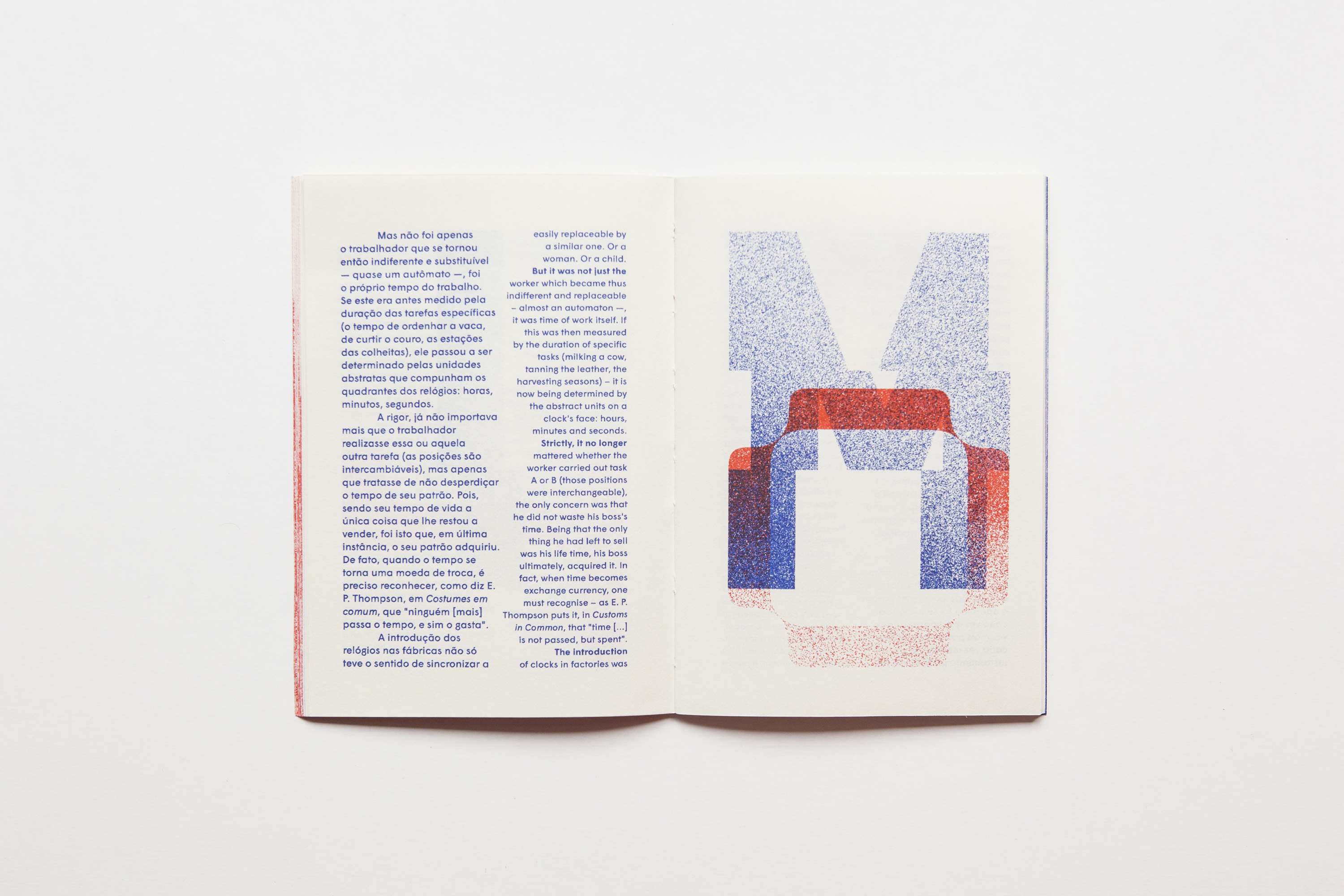

For that reason, one must understand what the automatic character of the machine entails: in order for it to work "independently", an operator needs to carry out some necessary actions, or at least monitor its performance. The machinery possesses a sophisticated (and expensive) mechanism that can only handle so much energy - a little more or a little less than the ideal amount and it will break. And that is a problem. Conversely, man becomes increasingly devalued and easily replaceable by a similar one. Or a woman. Or a child.

But it was not just the worker which became thus indifferent and replaceable – almost an automaton —, it was time of work itself. If this was then measured by the duration of specific tasks (milking a cow, tanning the leather, the harvesting seasons) – it is now being determined by the abstract units on a clock’s face: hours, minutes and seconds.

Strictly, it no longer mattered whether the worker carried out task A or B (those positions were interchangeable), the only concern was that he did not waste his boss’s time. Being that the only thing he had left to sell was his life time, his boss ultimately, acquired it. In fact, when time becomes exchange currency, one must recognise – as E. P. Thompson puts it, in Customs in Common, that "time […] is not passed, but spent"[2].

The introduction of clocks in factories was intended, not only to synchronise the production chain, increasingly more complex and mechanised, but also to act as a form of social control over the workers, under the authority of the new "time-currency". It’s no coincidence that still in the early 19th century, popular uprisings were targeted at the clock, showing the worker' s perception of the object as an even greater source of oppression than the rest of the machinery. Nevertheless, the strategy gradually reversed in

successive efforts to reduce the weekly working hours, the clock began to be used in favour of social demands. Those hands started to tell the objective difference that existed, at least at that time, between the time for work and the time for rest.

At that point, the abstract time of clock had become natural. And this was only possible because the device became cheaper, more popular and above all, smaller

and smaller. As a portable instrument, it paved its way into people’s homes, and later, in men's pockets; disappearing from sight to become omnipresent.

A similar feat happened to the photographic camera, invented in the final decades of the First Industrial Revolution. When Louis Daguerre announced his method to

the world in 1839, he characterised it in his text "The Daguerreotype" primarily by its practicality: "for the technical means are simple, and require

no special knowledge to be used. Only care and a little practice is needed to succeed

perfectly"[3].

As

it is known, the attributed paternity of photography to Daguerre is rather

political – a government representative convinced the French State to acquire this patent specifically —, but also speaks volumes about the nature of the invention:

deep down, creating a product was more important that producing images.

For

inventors such as Daguerre, finding a way to capture Nature’s transient images

in the interior of a dark camera did not suffice. It was necessary to ensure

that the procedure would be stable, relatively simple and economically viable. And,

in the end, his method was indeed objectively simpler than that of his former

trading partner, Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, who had obtained the first photograph

more than a decade earlier.

This

entrepreneurial spirit gained its utmost expression with George Eastman,

founder of Kodak, whose most famous slogan was "you push the button, we do the

rest". Unlike the other available devices in 1888, which were expensive, hefty

and difficult to handle; his proposal consisted of a closed box, easy to

transport and to use, complete with a one-hundred sheets film roll and a fixed

focus sensor which could not be adjusted.

His

product was not made for those with the means to purchase an extravagant piece

of equipment, or the free time necessary to "artistic" experimentations, but to

each and every man. Behind this initiative for the democratisation of images,

was also a commercial strategy which would become a case study: essentially, Eastman

understood that it was worthwhile to provide simples (and cheaper) devices to,

in turn, profit from spare parts and additional services.

With

the cost US$ 1, his camera was in a way selling the company’s real innovation:

a removable roll of film, which had to be developed in a Kodak lab. In doing

so, a new market was created, which was both highly lucrative and loyal, made

up of amateur users who needed not know the first thing about their equipment,

and for that very reason, depended entirely on their supplier.

Thus,

what had been announced as a new form of autonomy became, paradoxically, a new

form of dependency. An economic one, surely, but also an existential one; for Eastman

did not only respond to a genuine desire from the public – keeping a visual

memento of their life –, but he also actively worked to make this some sort of

inalienable right. As a result, the possibility of exercising such photographic

rights over the world took on the name of a private company: it was the "Kodak

Moment".

Advertising

played an essential part in the creation of a demand which was perceived by the

consumers as something coming from the purest, most natural, spontaneous and immediate

desire. Through adverts which were put out for decades on end, the very word "Kodak"

— chosen for the way it sounds, and the letter "K" with its modern appearance –

would become one with the photographic act itself. More than alluding to the

camera and the film which were objectively for sale, Eastman managed to make

his company into an English verb: "Kodak as you go", read the advert.

The miniaturisation of the camera was also instrumental in the process of

naturalisation of technique. When they started fitting into a coat’s pocket,

they became an invisible extension of the user’s body – a kind of mechanical

prosthetic, but which was felt as something organic. Thus, taking photographs

was no longer a random activity, a luxury hobby, but an activity intrinsic to

everyday life: one eats, works, has a family, and all these things must be photographed.

Otherwise, they never happened.

In her collected essays On Photography, Susan Sontag mentions the

appearance, on the 20th century, of a "photographic vision" which would do away

with the camera itself. So much do we consume images, she says, in postcards,

magazines, and (nowadays) screens; that we learned to see the world

photographically. This is a new visual code which redefines "our notions of

what is worth looking at and at what we have a right to observe"[4].

This

is no innocent matter. The logic of photographic "framing" destroys the appearance of nature’s unity, typical of the classical age, shredding reality

in a myriad of visual atoms. Photography, she says, does not only establishes

that the modern world is fragmented, fractured, disarticulate and disconnected;

it extrapolates this state of fragmentation.

Far from their original contexts, each of these fragments of world takes on the

role of a new temporary unity. Yet, unlike the classical image of nature, photographs are no longer transparent but essentially opaque, abstract, loose

pieces of a bigger unit which is always missing. Thus, an alternative version

of nature overcomes reality, made up from the speculative correlation of all these images without context.

It is speculative because this new experience of the 'real' exceeds the concrete

experience of any individual. In addition to their own experiences, one also has

to deal with different people's life fragments, including those from different

eras. Not only is the sum of the parts always greater than the whole, but the

order of these elements is also indifferent. Sontag concludes: "In a world

ruled by photographic images, all the borders ('framing') seem arbitrary. Anything

can be separated, can be made discontinuous, from anything"[5].

In brief, the photographic camera seems to do to space what the mechanical clock

had done to time. Reality is fragmented in equal and interchangeable units,

just as time had been fragmented into abstract and replaceable intervals. In

both cases, the reference to the world of experience remains nothing but a

mirage. The photographic images no longer correspond directly to what they

intend to show, just as the subdivisions of the clock have long since coincided

with an exact fraction of the Sun’s apparent course.

If

the 19th century saw the clock transform time into money, the 20th century saw

photography capitalise on space. Jonathan Crary, in Techniques of the

Observer, proposed a parallel between images and money: "[Both] are magical

forms which establish a new set of abstract relations between individuals and

things, and impose those relations as the real."[6]

It

makes sense: money is, indeed, the impersonal measure of all things,

mass-produced and free-flowing without corresponding directly to its physical

references. But the essential point of the parallel resides in the idea of

exchange: it matters not that they fail to correspond to reality, so long as

they correspond to one-another. Photography, he claims, has created a universal

measure among all visible things which, turned into images, can now be

isolated, quantified and accumulated endlessly.

Yet

it’s equally important that these relations are considered not as abstract, but

as perfectly concrete. This is the "magical" power of capitalism, which allows

itself to come forward not as historical and social construct, but as a seemingly

natural response to our deepest desires.

This

very idea appeared in Sontag, who proposed a certain "equivocal magic of the

photographic image". Yet his feature is not exclusive to the photographic

camera; it relates to what it shares with all the other machines, particularly

with the clock.

By

taking their energy source directly from nature, dismissing all human action,

these machines may appear as an extension of nature itself. What is better; they

are faster and more practical: everything that had previously happened

spontaneously, now does so instantly, thus giving us the impression of an

enchanted world, in which one can simply "push the button" for everything to

happen "by itself".

Finally,

a second Nature, where we could eventually rest. Which is patently false: he

who sleeps is the owner of the machine, never he who operates it. But the

promise is undoubtedly seductive and, therefore, remains alive ever since the

Greek epigrammatist Antipater of Thessalonica composed, in 85 BCE, perhaps the

first ever advertising campaign of all History — not fortuitously, for a

machine, the watermill:

"Hold back your hands from the mill, O maids of the grindstone; slumber longer, e’en though the crowing of cocks announces the morning. Demeter’s ordered there nymphs to performs your hands’ former labours. Down on the top of the wheel, the spirits of the water are leaping, turning the axle and with the spokes of the wheel that is whirling therewith spinning the heavy and hollow Nisyrian millstones."[7]

–––––

1 MARX Karl. Capital: A Critique of Political Economy. Translation by Samuel Moore and Edward Aveling. Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1887 [1867]. part 4, ch. 15, p. 263

2 THOMPSON, Edward Palmer. "Time, Work-Discipline and Industrial Capitalism." In: Customs in Common. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1993 [1991]. ch. 6, p. 359.

3 DAGUERRE, Louis Jacques Mandé. "Daguerreotype". In: EWER, Gary W. The Daguerreotype: an Archive of Source Texts, Graphics, and Ephemera. EWER ARCHIVE M8380001. Translation by Beaumont Newhall. 30 Sept 08 [1839]: http://www.daguerreotypearchive.org

4 SONTAG, Susan. "In Plato’s Cave." In: On Photography. New York: Rosette Books LLC, 2005 [1977]. ch.1, p.1.

5 id., p. 17.

6 CRARY, Jonathan. "Modernity and the Problem of the Observer." In:Techniques of the Observer: On Vision and Modernity in the Nineteenth Century. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1992 [1990]. ch.1, p. 13.

7 GIMPEL, Jean. "The Energy Resources of Europe and Their Development." In: The Medieval Machine:The Industrial Revolution of the Middle Ages. Harmondsworth: Penquing Books, 1983 [1975]. ch. 1, p. 7.